You are an incipient LEDDA that is exploring its long-term economic goals. Your task is to set parameters for a steady-state model of the Token Exchange System (TES) so that currency flows are in balance and desired targets are achieved. The token is a local electronic currency that circulates among members alongside a national currency (the dollar, in this model). Thus, a TES is a bi-currency system.

More specifically, because a TES is part of a democratic social choice system that uses money as a transparent voting tool, your task is to create a currency circulation that:

Balances at each node. The sum of inflows at each node must (approximately) equal the sum of outflows. A fitness score is produced based on discrepancies, with a perfect score being zero.

Attains a desired income target. The TES incorporates an alternative version of a minimum wage and guaranteed basic income, where both increase over time on a planned schedule until the income target is reached. By default, the income target is roughly equivalent to the 90th percentile of US family income, which is about $110,000. The dollar portion of this is equal to the US average family income, which is about $71,000. At steady state, every member family receives at least the target, regardless of work status.

Attains a desired workforce partition. You choose the percentage of the workforce engaged in each of the three types of organizations: nonprofits, Principled Businesses, and standard businesses. Principled Businesses are a special type of socially responsible business unique to the LEDDA framework. Standard businesses are any for-profit that is not a Principled Business.

Attains a desired partition of organization revenue. Member persons directly support organizations in two ways: (1) they purchase goods and services in the local marketplace; and (2) they provide donations and subsidies (and loans) through the Crowd-Based Financial System (CBFS). Each member decides how his or her mandatory CBFS contributions will be used. These two paths are the main source of local funding for organizations, and major components of economic direct democracy. Other, smaller revenue sources for organizations include government grants and contracts.

Think of yourself as the driver of a LEDDA, as if it were a car. A car can be steered toward a desired destination. Similarly, you choose the desired destination for the TES, and conditions smoothly change from those of today to those that are desired. Agent-based and other models show the steps along the way. This steady-state model shows the destination.

Note that this steady-state model illustrates currency flows in an idealized LEDDA economy, in the long-term, once targets are achieved and the system is in dynamic equilibrium (perhaps 15-30 years after initiation). It is intended to illustrate concepts and as a research exercise, an early step toward more sophisticated and functional models. It is not intended to be predictive or to capture all or even most salient characteristics of a real economy. It provides an abstracted, compartmental view of local currency circulation. Further, the TES is only one part of the LEDDA framework. The steady-state model does not address decision-making in the collaborative governance system, for example.

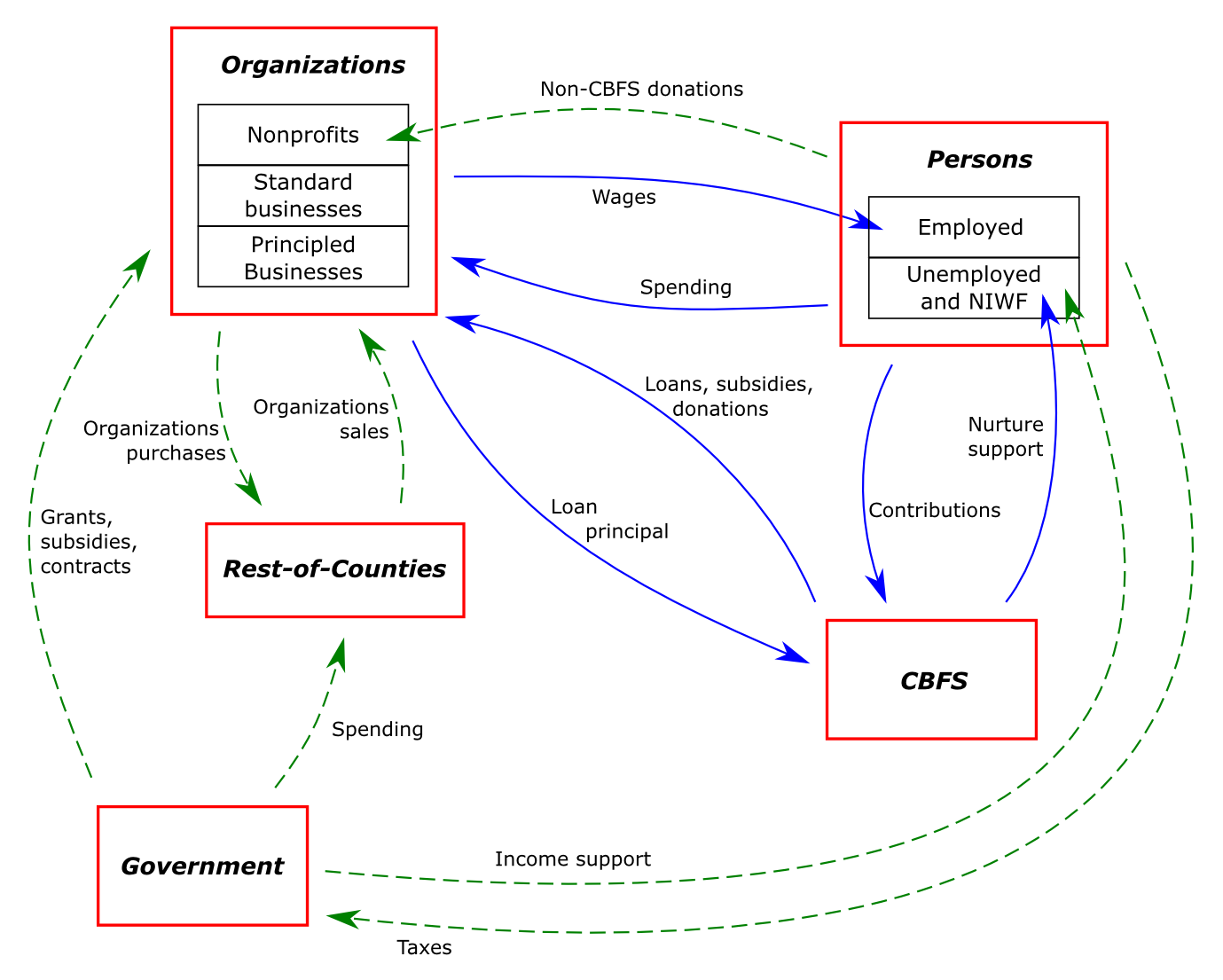

Flows in the model resemble flows in a national accounts diagram, an example of which is shown in Figure 1. In the steady-state model, however, flows are for a US county, not a nation. Starting income distributions are synthetic, based on 2011 census microdata for Lane County, Oregon [2].

An agent-based simulation model [2] illustrates how conditions start from those of today and change from year to year to reach steady-state targets. The five primary compartments of that model are shown in Figure 2. The same general layout is used for the steady-state model, only the five compartments are subdivided further into 20 nodes, as shown in Figure 3. CBFS lending and saving is not included in the steady-state model (CBFS lending to organizations produces a near-zero net change in currency flow, as the lending of tokens and dollars occurs interest free).

In the simple world of this model, the local population is comprised of two-adult families. Demographics and the economy are held at a static snapshot except for the direct impacts of the LEDDA. Thus, for example, the population does not grow or age and inflation does not occur. Also, the incomes of families that do not become members do not change; incomes remain equal to starting incomes, which are generated based on US Census data as in [2]. The starting workforce partition is generated using US labor data. Tax rates and average grant support per capita to nonprofits and subsidies to business are taken from government data, as is the average amount of monthly government support paid to unemployed and not-in-workforce (NIWF) persons.

The purchasing power of a token is assumed equal to that of the dollar. Further, it is assumed that families will join a LEDDA only if doing so increases their income over baseline. The default family income target is 110,000 T&D (tokens and dollars), roughly equivalent to the current 90th percentile of US family income. Thus, about 90% of local families will join the LEDDA. In effect, the LEDDA pays people to become members, and the pay is high enough that about 90% of families join. By default, the token share of income (TSI) is 35%, which means that the dollar portion of the family income target is about $71,000. This is roughly equal to the US mean family income. All US communities could have a LEDDA and achieve the same income target.

A LEDDA must achieve a high enough circulation of tokens and dollars such that all members can receive the income target. The ultimate source for tokens is the LEDDA itself, which generates tokens by fiat in a transparent manner, at near-zero cost. The ultimate source for dollars, assuming that there are not already enough in local circulation, is a favorable trade balance with the outside world (the Rest-of-Counties node in the model). In the growing years, a typical LEDDA adjusts its trade balance (and its production of local goods and services) so that more dollars flow into the LEDDA circulation than leave. But at steady-state, once the income target is reached, a trade balance is achieved such that dollars leaving the LEDDA (through all sources) is equal to dollars entering.

Two of the parameters set by the user in the standard model are the workforce partition and the partition of organization revenue. Together, these define the flavor of economic democracy for the LEDDA. For example, a LEDDA can choose to have most members employed by the nonprofit sector and to have that sector funded largely via CBFS grants. In this case, much or most of the decision making of economic direct democracy occurs via the CBFS. As an alternative, a LEDDA can choose to have most members employed by the for-profit sector, in principled businesses, and to have that sector funded largely via sales revenue. Then much or most of the decision making of economic direct democracy occurs via the marketplace. A LEDDA can choose any workforce and revenue partitions that best help it to solve problems and improve collective wellbeing. Indeed, some types of services (like medical care, perhaps) might be better suited to nonprofits and the collective nature of decision-making in the CBFS. Others (like restaurants, perhaps) might be better suited to for-profits and the more individualized nature of decision-making in the marketplace.

Parameters that are solved for by the model or that are fixed at default values include the token share of income and CBFS earmarks. Earmarks refer to the percent of gross (pre-CBFS, pre-tax) income that a member person must contribute to the CBFS. The family income target refers to post-CBFS, pre-tax income, which is gross income minus all CBFS contributions. Obviously, if a LEDDA wishes that much of the decision making of economic direct democracy occurs via the CBFS, then it will need to fund the CBFS using appropriately sized earmarks. Also, the CBFS earmark for the nurture arm must be high enough so that every member family can receive the income target, regardless of work status. Keep in mind, however, that whatever partitions of workforce and organization revenue are chosen, and whatever earmarks are chosen in support of those partitions, the same income target is achieved. Assuming use of the default income target, the choice is not about income level but about how or in what arena a LEDDA wishes to conduct its decision making for economic direct democracy.

Given starting conditions and parameter estimates, the model calculates the amount of tokens and dollars flowing into and out of each node. From these values, a grand fitness score is calculated as the absolute value of the discrepancies (the difference between inflows and outflows) summed over all nodes. To this sum, a penalty is added for any discrepancy between the actual flow of CBFS funding to organizations and the expected flow, given the revenue partition target. A grand fitness score of zero is perfect, meaning that inflows match outflows at each node and the revenue partition target is attained.

Once a fitness score is calculated for a starting set of parameter estimates, the model selects a new set of parameter estimates and calculates its fitness. Hopefully, the fitness of the new set will be lower (better) than the old one. This process continues until the fitness score is close to zero or no more progress can be made. The model then returns the parameter set that produces the lowest fitness score. From this flows are graphed and tables containing information are constructed for the results page. Behind the scenes, the model employs a standard minimization routine (BFGS) and as an option can employ a genetic algorithm, or both.

As an example of flows around a node, member persons (see Figure 3) who are employed receive income from wages. If unemployed or NIWF, they receive government support (in dollars) and CBFS nurture support (in dollars and tokens). All member families receive at least the family income target, regardless of employment status. Each member person makes CBFS contributions (in tokens and dollars), pays government taxes (in dollars), makes donations to nonprofits (in dollars), and then spends any remaining dollars and tokens at local organizations for products and services. Once a member has made contributions to the CBFS, he or she can choose which organizations the contributions will fund. A membership debate occurs in the CBFS to help guide funding choices.

Trade with outside areas is handled via organizations, which purchase products from outside the local area and sell to customers within the local area. (In an improved model, persons would also purchase goods and services directly from outside areas.) At steady-state, a LEDDA balances its trade with outside areas so that inflows of dollars equal outflows.

In summary, flows at nodes are solved sequentially, given a parameter set. Once flows at one node are solved, they are used to solve flows at other nodes. After the flows for all nodes are solved, a grand fitness score is calculated as the sum of flow discrepancies over all nodes, for tokens and dollars, plus a penalty for any discrepancy related to the revenue partition target. A perfect score is zero. Different parameter sets are tried until a grand fitness score near zero is achieved or no further progress can be made.

As a next step, run the standard steady-state model.